There was a time, according to Richard Beeland, when Chattanooga realized the key to its future was its waterfront on the Tennessee River.

“There was real effort to reclaim the river and make it the front porch, or the front yard, of the city,” Beeland, spokesman for the Chattanooga Mayor’s Office, said. “It started with building an aquarium but it continues right up to today. And what it’s done is reclaim the river as an integral part of the quality of life for the citizens of Chattanooga.”

The river was a vital economic organ for the city of Chattanooga — at one time. Things changed in 1969 when the city was given the label of having the worst air quality in the nation.

“That was a turning point for a lot of people,” Beeland said. “There were heavy smelting industries and smokestacks belching out pollution and that all came from a time when that meant progress and jobs.”

The Tennessee River was just part of that, and the land where the city and the river met was industrial and utilitarian.

“At the time, it was a bunch of old worn out warehouses down there and the only time anybody ever looked at the water was when you were crossing over a bridge,” Beeland said.

Now, Chattanooga had to imagine a new future.

“We had a visioning process where we talked about what we wanted to see in 2000,” Beeland said.

Today, a world-class aquarium brings in hundreds of thousands of visitors per year. It’s surrounded by a district full of restaurants, art galleries, small businesses and shops. It includes a park along the river’s north shore and a renovated old bridge that had been slated to be torn down.

“People in the community came together and said it was all too important,” he said. “We turned it into the largest pedestrian bridge in the country. Now, it’s a part of a park going all across the river.”

It’s the kind of success consultant David Spillane imagines for Lewiston-Auburn’s Androscoggin River waterfront. Chattanooga was one of the cities Spillane and his team at the Boston planning firm of Goody Clancy used as examples last November when they helped kick off work on Lewiston’s Riverfront Island Master plan.

Now, Lewiston’s plan is all but finished. It recommends creating a complete athletic walk along the Lewiston side of the Androscoggin River — a mirror to Auburn’s Riverwalk on the Androscoggin’s western shore.

The plan also foresees walking paths along Lewiston’s canals, new businesses and housing along Lincoln Street and a redeveloped and vital district from Cedar Street north to Island Point.

Like other river cities, Lewiston’s future starts at the waterline.

“All these cities, they recognized that their downtowns have the ability to be destinations,” Spillane said. “When you put together the mix of a downtown and a riverfront — or waterfront or canalfront — you can create a pretty great mix.”

That’s been the lesson in city after city with an industrial waterfront that’s been cleaned up, but left undeveloped.

“What’s constant is they are trying to take advantage of the water,” Spillane said. “Everybody’s way of doing that is different, because the water is different.”

It worked in Burlington, Vt. Development Director Larry Kupferman said his city struggled for years trying to find a way to develop the waterfront on Lake Champlain.

“The land we are talking about was filled land, reclaimed from the lake in the 1800s,” Kupferman said.

It was an industrial section with rail warehouses and lumber yards.

Today, the Lake Champlain waterfront is a bustling festival space.

“We consider the waterfront part of our downtown,” he said. “All of the buildings around it have been renovated, and many have been rebuilt. It really was the economic driver in the 1990s. Now, we’re trying to make an even greater connectivity to the waterfront.”

It’s not always easy.

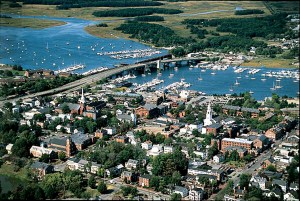

The Newburyport, Mass., Merrimac River waterfront is being redone in pieces, according to Planner Geordie Vining.

“We’ve had a combination of significant success in terms of transforming the waterfront and also a lot of unfinished business as well,” Vining said.

The town has refurbished a 1970s boardwalk and extended it, added utilities to the waterfront and wharf and hired a new harbor master to manage traffic.

“We also have these clear, empty lots that were supposed to be interim parking lots,” Vining said. “The community has been struggling for decades on how to transform those, what could be high value real estate. But right now, they’re just gravel lots.”

The community’s focus has turned to the land on either side of the central waterfront, extending the boardwalk and building parks.

“The central waterfront has been the kind of place where strategic plans go to die,” Vining said. “We are not a model of transforming fully. We have a complicated mixture of significant transformations and then some difficulties.”

Larger waterfront projects have been stalled, but the community is still trying.

“There is actually a new initiative right now to focus on that area,” Vining said. “We’re looking at funding sources to help develop that waterfront park and add open space to that area.”

Comments are no longer available on this story