Some are spending significant sums of money advertising in the social media cloud.

But beyond the traditional effort to bolster a candidate’s image or propel their message, campaigns are also using social media to expand their reach for fundraising, engage a growing online audience and to monitor the efforts of their rivals.

Using popular sites like Facebook and Twitter to monitor what others are saying about them and reacting to it are some of the many ways modern political campaigns are using communication technology to get an edge on their opponents, Emily Shaw, an assistant professor of political science, at Thomas College in Waterville said.

But the verdict is still out on whether those with the most popularity on social media online are converting that to support at the polls, Shaw said.

“It’s something that political scientists are very interested in because it has the potential to, first of all, increase engagement among younger citizens, which has been a persistently low participation group for several decades,” Shaw said. “The question is often phrased as, ‘Will social media encourage greater participation by younger voters?'”

So far, Shaw said, there hasn’t been any real demonstration that it works. However, it probably can’t hurt, Shaw said.

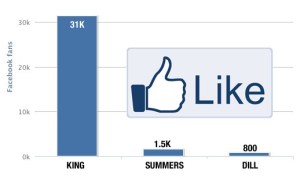

In Maine, former governor and independent candidate Angus King is leading the Facebook race with more than 31,462 people clicking the “like” button on his official campaign page on the social media site as of Wednesday.

King’s campaign, according to federal campaign finance reports filed in July, is also spending more on Facebook advertising than any of his rivals.

The campaign has spent about $10,000 advertising with Facebook and Google.

Facebook fans for Republican Charlie Summers pale in comparison to with 1,561 people liking his page. Democrat Cynthia Dill is a distant third in the race for “likes” on Facebook with only 884, according to a check of the candidates’ respective pages.

Summers’ campaign, according to campaign finance reports filed in July, has spent nothing on social media advertising. Dill has spent just over $200 advertising on Facebook, the reports show.

Lance Dutson, Summers’ campaign manager, said the next reporting period will show him spending on social media advertising.

Dutson, who first started in politics as a social media director, said the use of Facebook and “likes” is now just common practice with campaigns and most have made it an integral part of their communications strategies.

“The great thing about it is it is two-way interaction,” Dutson said. “It’s more fluid and productive in many ways compared to, say, just television or newspaper advertising.”

Dutson also said the breadth of the social media demographic is growing, so it’s not necessarily just a way to engage young people.

For advertising, social media also allows campaigns to “micro target” and refine their message for distinct audiences, Dutson said. “It’s incredibly granular.”

But the quality of a message still matters as much as anything else, he said.

Dutson said those who spend more advertising on Facebook will naturally get more fans and “likes.” He said King’s campaign has more “likes” because they’ve purchased more online advertising.

“But you can’t purchase your way into something becoming viral,” Dutson said.

On the candidates’ pages you can see photos from nearly every campaign stop the candidates have made and read comments from those who support them or, in some cases, those who oppose them.

The pages are used to publish the latest news releases or candidates’ reactions to events or statements their opponents are making.

Shaw said political scientists haven’t fully studied the impact of social media, but she agrees social media seem to serve multiple functions for campaigns.

“A lot of people talk about social media as a way to transmit information so it really aids when people are looking for information,” Shaw said. “So, it tends to increase information among already engaged people.”

Campaigns may also be using the sites to monitor what others post about them or to help campaigns quickly tamp down negative rumors or misinformation.

The emergence of social media directors for candidates is a campaign staff position that wouldn’t have been considered just five years ago.

But recent campaigns, including the U.S. Senate primary campaigns in Maine, have employed people just to monitor and manage candidates’ online images.

“I wonder how much of that might also be an interest in being reactive,” Shaw said. “So you have to have somebody on there kind of ready to catch stories as they are breaking.”

Shaw said often the biggest political stories are breaking first on social media sites like Facebook and Twitter.

Of the other lesser-known independent candidates in the race, Andrew Ian Dodge, a tea party conservative, has the highest social media profile.

Neither Steve Woods nor Danny Dalton, also running as independents, seem to have a Facebook page.

Dodge is a prominent poster on Twitter and frequently engages supporters, opponents and the media on that site

“You know a lot of stuff is breaking online before it breaks in traditional media,” Shaw said. “It makes a lot of sense to have somebody with their ear that close to the ground.”

Another function for social media campaigns for candidates may be to draw support from out of state, especially financial support.

“People in state do go online but there’s a lot more ability to contact them via phone or traditional means so this might also be a kind of fundraising strategy,” Shaw said.

King’s campaign spokeswoman Crystal Canney said Tuesday their strategy involves King himself taking questions and interacting with his fans each day for up to two hours. Canney said social media has been an effective way for King to extend his reach.

“It allows him to be in Washington, Aroostook and York counties in one night talking to citizens,” Canney said. “It complements a strong field operation with 1,600 volunteers and more than 60 student interns that have rotated through the campaign over the summer.”

Bob Mentzinger, the media coordinator for Dill, said in an email message their campaign used Facebook advertisting before the June primary and believe it may have helped them win the Democratic nomination.

“We did a targeted (Facebook) ad in the primary that got 150,000 views and may have had an effect on a race in which no one did any traditional ads,” Mentzinger said. “Remember, polling showed a dead heat prior to June 12, and we won by 8.5 percent.”

Mentzinger said counting “likes” was a “ridiculous” metric because even those opposed to a candidate will “like” a page so they will get updates.

“Enemies like people’s Facebook pages all the time to gather intel,” Mentzinger said. “It doesn’t show support, in other words. If there is one social media metric that is universally suspicious, it is the Facebook ‘like’.”

Dill’s campaign has used the page to promote campaign videos like one released Wednesday touting Dill’s support of women’s rights.

Mentzinger said campaign videos have been cross promoted on multiple social media outlets including those offered by Vimeo, Google+, Twitter and Tumblr.

“It’s a way for me, the candidate, to really stay in touch with voters and for voters to stay in touch with me,” Dill said.

While it’s no replacement for boots-on-the-ground campaigning, it’s just one more tool campaigns, especially those who trail in fundraising, to cost-effectively reach voters, Dill said.

“For campaigns that are grassroots and don’t have deep-pocket corporations to turn to for contributions, social media is definitely an efficient way to communicate with voters and that’s what campaigns are all about,” Dill said.

She said she doesn’t have set times to be on social media but manages it in an ongoing effort intermittently throughout the day.

“Social media is becoming as traditional as your campaign signs, buttons and bumper stickers,” she said. “It’s where the people are so you have to be there.”

Another use of social media by campaigns is they provide candidates a relatively low cost and low risk way to float ideas or to refine positions in a process that Shaw described as “narrow casting.”

For campaign coordination it may also be serving candidates well, Shaw said.

Before social media, campaign staff or volunteers could spend hours visiting and doing advance work to ensure a positive whistle stop. Now some of those logistics can be achieved online.

“You can communicate exclusively with a selected group of people and that kind of increases the possibility you can have a really friendly campaign stop, for instance, and possibly avoid problems that might otherwise come up,” Shaw said.

Comments are no longer available on this story