SALEM TOWNSHIP — A group of SAD 58 students got practical lessons Monday about trees, math, property ownership and career opportunities.

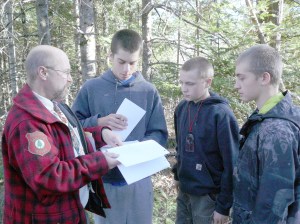

In Barry London’s woodlot management class, students formed groups to calculate measurements of lot sizes and identify marketable trees that could be cut on the lot. Jonathan Hart, Andrew Murphy and Jonathan Theriault , owners of the fictitious HT&M Logging, learned to design and lay out woods roads and bridges. They also determined costs using online data from the U.S. Department Agriculture and the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

“They have to calculate the wood volume for a one- acre plot,” London explained. “They have to know they can make money for themselves, as well as pay their expenses.”

The three students learned they would need to spend approximately $14,000 to build bridges and roads, with road costs approximately $6 per square foot.

Adding culverts would increase their costs by $1 per square foot. Those initial costs can be paid by the landowner, the logger, or shared by both.

Students learned that their profits depend on a long list of variables, including the average size and quality of trees, the terrain and distance to public roads, the time of year, and landowner requirements. Some students have friends and relatives in the wood industry, so the process is not as difficult for them.

“My dad is a logger,” Therrien said. “My brother works in the woods with him, so I know a little bit about the industry.”

The three also learned to calculate the marketable, or “merchantable stumpage” of trees on a lot, which requires them to use a Biltmore stick. They start with the distance from an imaginary foot-high tree stump to the height of the log to be cut and hauled to a mill. The calculations from this “diameter at breast height,” or DBH, of trees on the property, determines their potential value. Murphy held the stick against a tree at arm’s length and moved the left, or “zero” end of the stick, parallel with the left side of the tree. Theriault read and reported the measurements to Hart, and they continued to another tree. Students employ basic trigonometry and geometry principles to estimate a tree’s diameter and height without climbing the tree or wrapping a tape around the trunk.

They also learn to complete a deed that could be filed in the Franklin County registry, requiring them to acquire a modest vocabulary of surveying terms. London teaches a combination of old-fashioned woodsmen’s skills and technological advances. Students master a compass, as well as a global positioning system to measure acreage. They learn to calculate distances between points on a lot by measuring the length of their paces and converting totals into feet. On Monday, the three spent the afternoon practicing what they had learned.

“We’re going to find a landmark off the Mount Abram (school) property and we’re going to take a bearing to our first point,” Hart said. “Then were going to pace it off and take the distance from the landmark to the first point.”

The goal, Hart said, is to supply an accurate description of the lot size and location for a property deed.

London invites professionals in the field, such as NewPage log buyer Robert Carlton and forester Peter Tracy, to advise students about other issues. He had students use topographical maps to select their woodlot management plan area. Even if the students do not go into the forestry business, they learn valuable mathematical concepts, an appreciation for entrepreneurship, and confidence in their abilities to navigate successfully in Maine’s thick forests.

Comments are no longer available on this story