OTISFIELD — It was almost 40 years ago that Paul Laird II drove a bulldozer through the hot sand dunes of the Enewetak Atoll, clearing down palm trees and skirting giant crabs with vice-like grips capable of cracking coconuts.

The air, heated by the equatorial sun, made the young military men desperate to swim in the off-limits ocean, kicking up dust motes concealing radiation the effects of which would lay dormant in Laird’s body for years.

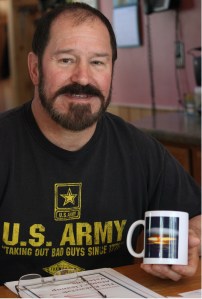

Sitting inside his home near the Crooked River on a recent morning, Laird, who is 58 but looks a decade younger, short, stocky and in shape and a cancer survivor many times over, recounted the scant protective gear he and other veterans wore in 1977, cleaning up nuclear fallout just 19 years after the military detonated the last hydrogen bomb on the small group of Pacific Ocean islands.

A year ago, Laird found a group of Enewetak Atoll veterans — also called Lojwa Animals after the large native rats they hunted at night to keep them out of the tents — organized on Facebook and looking to reunite members. Thousands were stationed there, and 181 have signed up on a list of survivors so far.

Now he’s trying to raise awareness to change the law so veterans can qualify for government medical care, as he fears the group, wracked by cancer and other diseases, is dying out before its time.

Workers on the Marshall Islands are not defined as atomic veterans and subsequently don’t qualify for benefits through the Veteran Benefits Administration because their work for the military — 1977 through 1980 — misses the 1962 cutoff for eligibility, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs’ website. Veterans who qualify are not required to prove their conditions were caused by radiation.

Additionally, Laird said many members are unable to get health care through the VA because they’re not classified as Vietnam-era wartime participants. As he enlisted at the age of 17 in 1974, Laird, unlike many, is eligible by a matter of months.

An inquiry at the Augusta VA’s office was referred to the deparment’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. A message left there was not returned.

Laird said his efforts ask a simple question: Should the government pay for the after-effects of its nuclear program?

“I think this is what the government was hoping, that’d we disappear, so the problem would go away and no one would know the difference,” Laird said.

It’s not the battle he expected. Between daily motivational posts imploring survivors to spread the word, he’s contacting congressional officials — Sens. Angus King’s and Susan Collins’ offices have been in touch — trying to create momentum to get congress to amend the law to reclassify the veterans.

For Laird, it has become a calling, the devoted cause he was awaiting ever since a near-death experience from complications with kidney cancer seven years ago.

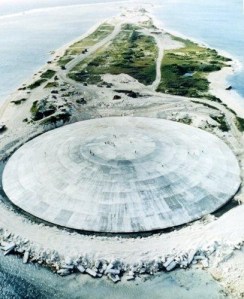

The atoll, part of the Marshall Islands, was the Cold War testing site for 43 hydrogen bombs between 1948 and 1958, which left mammoth craters that military engineers dumped sand, trees and the radioactive wreckage of ships into during the decontamination process, spending hundreds of millions of dollars. Eventually, engineers dumped it all inside a massive dome topped with concrete.

The federal government would later create an endowment fund for displaced Marshallese residents, paying out hundreds of millions of dollars to resettle its inhabitants. The Enewetak is projected to be inhabitable again by 2025.

Laird said the image projected is that everyone wore hazmat gear. In reality, supplies were so sparse in the beginning they had to roll up their pants for pillows at night. Shirts were used to filter the dust clouds churned by excavating, so they often worked bare-chested, sunburned by the relentless summer.

Prior to the troops’ arrival, they went through combat training but almost nothing in the way of dealing with hot materials. Superiors downplayed the risk and being “young and stupid” — he was 20 at the time — Laird let it pass.

When visiting dignitaries and commanding officers came to oversee the operations dressed in hazmat gear, Laird said he knew something was wrong.

Where to go for more information:

www.facebook.com/AtomicCleanupVeterans

Comments are no longer available on this story