POWNAL — Summer is in full bloom again, and as you turn onto Minot Road, that half-mile dirt lane near Bradbury Mountain Park that leads up through the welcoming woods to Hawk Ridge Farm, the green seems to be blooming even beyond itself. You’ve driven through beauty opening into a wider, open, even deeper beauty, a scene suggesting a kind of rural ideal.

If you have been here before, you’ll already be aware that these two small fields, the yards front and back, the house, the bushes and trees and even the stone walls are filled with things of wonder, mystery, allure. Some you can see immediately—You will recognize a few of the more visible sculptures still here from last year. You’ll be glad to see the other things that make up the permanence of the place—the old wooden fence and grapevine-covered bower between the yard and that small lower meadow; the beautiful gardens that are works of art in themselves. And you’ll also know that here and there among all these things are others that you won’t see until you come close enough for them to seem to rise from nature and reveal themselves.

The same two white horses that were here last year and the year before are grazing in the upper pasture. Chickens are still squawking from their coop just below the horses’ stalls, and once in a while there is still the shock of that sudden wild, loud, and foreign cry of an unseen peacock. Then you begin to notice other things.— On the other side of the fence just below the horses’ pasture, there are still more chickens, an elk, two flights of birds, and a raven perched on a stone post.

Still in life

Not one of them is moving, even though the birds are in flight. The chickens are stone, the elk—which seems to be grazing among upright spears of splendid blue lupine in a meadow rich with purple clover, vetch, buttercups, dandelion, and many nourishing grasses—is made of rusted steel rods; the raven is made of bronze and granite; one flight of dozens of swallows rises ten feet into the air despite being made of bronze and granite; another flight of larger swallows mounted on poles appear individually finished in bronze, gold leaf, or stainless steel—and all of them—chickens, elk, raven, and swallows—are products of nature made from nature—earth nature and human nature—the nature in the human mind, eye, and hand—the stone chickens made by the eye, mind and hand of Lisa Becu; the elk by those of Wendy Klemperer; the raven by Ray Carbone; the dozens of rising swallows by Cynthia Stroud; the larger, seemingly gliding barn swallows by John Bowdren.

Hawk Ridge Farm is alive again in many senses, including the work of over 40 New England sculptors in the present exhibition, with 125 new pieces on display, and each one of those pieces has been individually and brilliantly sited and installed under the supervision of June LaCombe, whose home this is.

She’s done it again— For 26 years a supporter of the work of sculptors all over New England, her work and reputation in the intuitive siting of sculpture has helped art collectors build their sculpture collections by overseeing their selection, delivery, placement, and installation. For 15 of those years, she has held these annual Hawk Ridge exhibitions, often with other shows at separate times. The “poetics” here are inscribed by her intuitive eye arranging the text of the sculpture on the page of nature, the page of the place itself, its tale raising wonder, surprise, discovery, meaning.

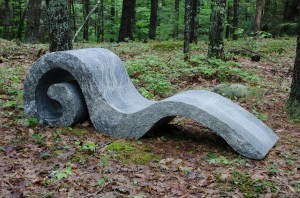

Arriving here again, you’ll probably start your tour at the table in the front yard. There you’ll find Roy Paterson’s “Her Skyline,” a very small but very strong example of Paterson’s abstract prone feminine nudes that carry in their outlines—as the title here implies—the theme of life—as well as art—rising from nature. Paterson has five new sculptures in this show, as well as a number of older works that have taken up permanent residence in these grounds—one of which stands tall in the garden beside the middle door of the house. Slender, rough, seemingly unfinished granite—you have to look at it for a while before you see the suggestion of the human figure—of life rising from stone—that it carries. Across the yard from there is a new work of his—“Ebb Tide,” a smoothly-surfaced feminine body profile in polished quartzite accentuated by rough granite, lying on a great stone slab.

And across the yard from “Ebb Tide” is George Sherwood’s untitled full, kinetic circle of what appear to be short open-ended sections of stainless steel pipes, each with its own circular loose-moving tab—another piece here surprisingly suggesting life —the breeze breathes on it and each tab shimmers on its own in the sunlight—collectively creating a shimmering round galaxy shining in the full light of day. Sherwood also has a smaller, similar piece hanging on a wall inside the house. All you have to do is gently blow on it as you walk by. Go ahead. Blow on it—and see what happens. You might note that Sherwood currently has another show, also arranged by June Lacombe, “Wind, Waves and Light”, at Boothbay’s Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens.

Stainless steel stands its own in this exhibition—across the meadow of the rusting steel elk, within the open trees at the edge of the woods, you’ll find—among many other surprises—a foot-long stainless steel ‘pine cone’ lying on the ground—composed of a number of squares of steel of varying sizes, all with their corners turned up in a rounding effect, all connected by a steel core.

Art working with nature

Some of the works here, like Sherwood’s shimmering circle or Dan Dowd’s “Pine Cone”[s] (there are seven more on the new “Sculpture Trail” across the lane) suggest art imitating—or at least working with—nature. Much of the other work, like Paterson’s, suggests art rising directly from nature. Two more of the most obvious examples of this—and there are many throughout the exhibit—can be found atop a small wooden table and an old stone retaining wall back where the hill slopes up from the house. Two pieces there by Cabot Lyford exemplify this theme—“Fran in the Morning,” a female form rising from the curved inner surface of a stone—the edges of the partial figure rise vaguely from the granite, then turn subtly more defined, but not fully so, as though it had emerged directly from the stone itself. The other is an untitled resting figure creating the same effect—a long, almost flat stretch of limestone, the sketch-like outline of a face almost scratched into one end, the lines flowing vaguely back from it and then disappearing. If you were walking through the woods past these stones, you might not even notice them—and there lies the beauty of the idea….

As always, this is a very large exhibit of the work of a large number of artists, and seeming even larger this year. I want so much to cover this fully, but can’t. I’ll try to move forward here by picking out a few of the works that have stuck in my own (very subjective) memory: Up behind one of the sheds, Lisa Becu’s Maine limestone “Girl with Bird,” an abstract block perfectly sited alone in its own small dark green garden by the corner of a shed, carrying—for me—a very totemic feeling — the bird perched on her shoulder, the girl’s face has an Indian—an “Intuit”—appearance, someone nearby me suggested, and then told me that Becu was Canadian and did indeed have a native background.

The last sculpture at the edge of the back yard (and there are more than a few back there)—Dan West’s “Big Blue,” large, beautiful, bronze and ‘blue-ified’ abstract profile of a heron, placed atop a knoll just above the pool below—had a very strong effect on me—and now, finally, I’ll take you up to the just-opened sculpture trail that starts across the lane—a great loop through open glades largely under hemlock and pine.

A new loop trail

To start, you’ll have to pass “Loyal,” Peter Dransfield’s big black bronze dog. I can’t cover everything on the way, but soon you’ll come across Wendy Klemperer’s weathered steel “Doe” standing off to one side and looking on a few yards across the trail toward her newborn “Fawn”, which lies curled up and very close to—almost on—the path, looking up and hoping you won’t step on it. Klemperer also has two coyotes you’ll meet along the way, one “playful”, the other “stalking”—still farther on, after—among other wonders (including more of Dan Dowd’s stainless steel pine cones)—you’ll pass her huge “Shed Antlers” (steel, resin) appearing even larger than reindeer antlers—lying on the ground, and—much farther on—her “Raven Flight” (flame cut, salvaged steel)….

And there is much more on the trail. Much more. Including Lin Lisberger’s “Journey”—a twisted applewood ladder set up high against a large pine, looking much like that old sailing ship net rigging that ran from the rail up to the lookout on the mast. A copper boat is ensnared in it, reminding me of those old, flooded Amazon legends of “the ship in the trees.” A little way around the bend from that, you’ll come upon Sharon Townshend’s terra cotta “Sprout/Root”, three off-white sprouts rising about a yard from the ground seeking light, life, moisture—a new beginning for one of the more primitive forms of plant life….—Not something you’d expect to see in “sculpture”. And in very interesting contrast to that, large golden leaves of some of our more noble local hardwoods—birch, elm, beech, oak—John Bowdren’s work in wood (mahogany and cedar) stand on posts here and there along the way between other works as the path winds back toward the farm, their color giving “gold leaf” a more precise and ironic meaning, and their contrast to the primitive “Sprouts” before them opening deeper questions for us to ponder….

And “pondering” is part of our mission on the planet. We owe it to ourselves. We owe it to each other. This exhibition offers us a reminder of that. To miss it would be to miss an opportunity toward a new depth of insight; to remember to open beyond beauty to meaning.

“The Poetics of Place” June LaCombe’s Hawk Ridge Farm 2015 Sculpture Exhibition, through July 26,, open by appointment. Sunday afternoon open houses 2 to 4 p.m., throughout the exhibition. Contact at: [email protected] , 207-688-4468.

Comments are no longer available on this story