Frank Perham has closed one door and opened another.

“I gave that talk last night and that was the end of one facet of my career,” he said, referring to his presentation at West Paris’ Mann Memorial Library on March 10.

Any career that has facets must be a gem, and it’s an apt metaphor to describe what the 82-year-old Perham has done with a life of mining minerals in Oxford County.

At his library presentation, Perham announced he has sold his expansive personal treasure of pegmatite specimens to the Maine Mineral and Gem Museum in Bethel.

For a miner, that’s business; but for the collector, that is a huge change.

Perham is moving on, but not away, from what he loves to do.

“It’s extremely interesting,” Perham said. “I like mining (minerals), and I like anything that’s got to do with feldspar, tourmaline, beryl crystals or mica.”

Those are some of the pegmatite minerals, and Perham is that kind of miner.

Family tradition

“I was born and brought up in the mineral business,” Perham said.

His grandfather, Alfred C. Perham, owned a herd of cows that unearthed the tip of a feldspar deposit simply by meandering over a field.

Perham said the deposit turned out to be “one of the largest finds of No. 1 feldspar in Oxford County.”

After first shipping the mineral via rail to Auburn to be processed, Perham’s grandfather “was instrumental in getting the (West Paris) feldspar mill going in 1926,” Perham said.

Perham’s father, Stanley, “started a mineral store in 1919,” Perham said. “It’s a vacant lot in West Paris now, (but) his first mineral store was right behind the barbershop.”

Stanley and Frank’s mother, Gwendolyn, moved the store to Trap Corner in West Paris in 1930.

Frank Perham was born in 1934, and there is a picture of him as a toddler on the front steps of the Trap Corner mineral store. Frank’s mother contracted a fever and died before he was a year old.

Like his father, Perham earned a degree in geology at Bates College. He tacked on a tour in Korea as a soldier in the 1950s.

The gem didn’t fall very far from the mine when he married quarry owner Nestor Tamminen’s daughter, Mary, in 1955.

“I’ve been married to a Finn for 60 years,” Perham said.

Mary helped at Perham’s mining locations by sorting material as it was being removed from mineral finds.

Having a blast

“If you want to dig for minerals you’ve got to get in there and drill holes and you have to be able to blast,” Perham said. “That means you’ve got to have a jackhammer, drill steel and dynamite.”

Perham became so adept at placing explosives that the state of Maine hired him for its small-scale road construction projects. The state liked that he could be called in on short notice.

“I became a distributor for explosives and I would sell the dynamite and caps to the feldspar mill in West Paris,” Perham said, “and the profit I made on that gave me dynamite to use on the weekends. I was using the jackhammer and compressor five days a week when I was working for the state and blasting (for myself) Saturdays and Sundays. I didn’t have any days off, but such is life. I did that for a long time.”

A very deep pocket

“Actually, I would say it’s a lot like going to the casino and winning,” Perham said of the sensation of opening up a pocket of pegmatite minerals.

“The all-time best one was in 1972 when I was invited to go up to a new mine in Newry,” Perham said. “They wanted someone with mining equipment to drill and blast, and of course I never turn down a chance to go mining. I was a little sick of drilling for the state of Maine. I was never any bigger than I am now and you can never get the best of a jackhammer. So they asked me, ‘Could you come up and open up this pocket for us?’ I said I’d come up for two weeks at $100 a day, plus all the dynamite and caps I used would be extra.

“So I went up and drilled around this pocket and blasted it, and they started cleaning out the bottom. At that point I was just standing around, so I asked, ‘Would you mind if I was to go down around the corner about 85 feet away and try that spot?'”

Perham knew the mountain very well because he had led tour groups there from the mineral store while he had been a high school student, and he had worked there six years previous to the 1972 assignment. He tried the location he liked the look of, and opened up one new pocket after another. One in the middle of the series kept filling with water. Perham’s boss inquired about the source of the incoming water and Perham said, “‘It could be the biggest pocket you ever saw,’ just as a flippant remark.”

It turned out the water was draining from the mother lode.

“Three days later we actually blasted into this (final) pocket and when we got it all done, it was 29 feet long, six feet in diameter side to side, and six and one-half feet tall. I could stand in it with a steel helmet on. There were tons and tons of feldspar, plus a ton and three-quarters of tourmaline crystals. The finest one is in the Smithsonian to this day and they call it the same thing I did when I found it, the Jolly Green Giant. That was in 1972.”

Perham estimated that the value of gem minerals removed from the single huge pocket would be worth about $7 million in today’s market.

That opening gave Perham the distinction of being the miner who found the largest deposit of gem tourmaline in a single pocket in North America. Although the original pocket he was summoned to work on was named Priscilla, he said no name was ever attached to the giant pocket he opened.

Perham has even had a new mineral variety named for him. Miners had initially concluded the material to be a common cookite. Eventually, it was found to be a rare silicated form of phosphate, and it is now named Perhamite. It has been found in other parts of the world, including Australia, but Maine’s occurrences have the largest crystals.

Binding an oral history

Two years ago University of New Orleans mineralogists Karen L. Webber, as writer-editor, and Raymond A. Sprague, as photo editor, published a book after years of preparation — and Hurricane Katrina flooding — almost totally about Western Maine’s notable miner. “Frank C. Perham: Adventures in Maine Pegmatite Mining,” by Webber’s Rubellite Press, has had a limited release, but the authors/publishers have promised more are on the way.

“Karen Webber wanted to have a complete history of the 1972 tourmaline pocket and it’s getting to the point that I and one other person are the only ones still alive that were there when it was discovered,” Perham said. “I told her, ‘If you’re waiting for me to write all this down, you can forget it.’ It’s not that I don’t want to, but I like to talk minerals, and I could care less about a book.”

Perham is a frequent lecturer and about 14 years of his talks had been recorded as audio or 16mm sound films.

“She probably ended up with a hundred transcriptions of things,” Perham said.

Webber arranged the material topically and chronologically, and designed the book with numerous personal and mining photos prepped by Sprague, and ended up with the definitive Frank Perham oral and photographic history.

Copies are available for sale at the Maine Mineral and Gem Museum.

Human dynamo

Part of Perham’s energy was honed at Oxford Plains Speedway, where he raced Plymouths in the 1960s. Ken Lamb is the collision center manager at Goodwin Chevrolet in Oxford and he knew Perham as a neighbor and as an “everything automobile” authority.

“One of the other drivers told Perham his race car wasn’t worth two cents,” Lamb recalls, “so Frank’s racing partner, Ron Heath, pop-riveted two pennies to the roof of the car so no one could ever say that again.”

Lamb has that same car in his yard today, although it’s been reduced to metal panels on a frame. The two pennies are still attached to the roof.

Lamb said Perham’s remarks and stories are falling-down funny. Perham realizes he can amuse an audience, and he chose humor reminiscent of Mark Twain to describe a core-drilling machine he used to prepare areas for blasting.

“This piece of equipment was my nemesis,” Perham said. “Among other things, I used to do a lot of core drilling. This (photo) is up to Rangeley, and when I go to the great beyond, I’m taking a picture of this thing with me in my pocket. If I go up, I’m going to throw it off a cloud, and if I go down, I’m going to tell the devil, ‘I’m here, and this thing better be right behind me.’ That rig had a four-cylinder Wisconsin engine on it, that must have been a hybrid of a mule, because it pretty near broke my arm more times to start it … I’m quite sure Noah had one of these on the ark for ballast.”

The photo and description are in the Webber and Sprague book about Perham.

“I see humor in almost everything,” Perham said. “If you can’t enjoy life, the only person being offended is yourself.”

Personal treasure

“I’m 82 years old and at that age you don’t want to take any long-term subscriptions to magazines,” Perham said, “and my wife was wondering what I was going to do with all the good stuff that I had (at home). So, I said, ‘I’ll get somebody to come and make an estimate of what it’s worth and see if it’s worthwhile offering it to the museum.'”

Although they paid to acquire it, the total collection at the Maine Mineral & Gem Museum has now significantly gained by owning the 1,280-piece Perham collection.

“I think it was very meaningful in capturing a collection to preserve Maine mining history,” said Carl Francis, the museum’s curator, “and in that sense it was probably the most important collection that’s out there.”

One of the museum’s employees needed five weeks to catalog and pack Perham’s collection.

Francis said the very best of Perham’s collection will eventually be installed facing an exhibit remembering Perham’s Maine Mineral Store, an institution at Trap Corner in West Paris run by Frank’s sister, Jane, until low sale volume forced its closing in 2009. Much of the store’s former collection, also purchased by the Bethel museum, was mined by Frank.

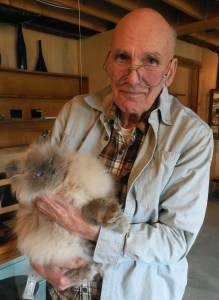

Perham said he started a basement museum in his house for an education goal so schoolchildren could learn about minerals. Perham said they tend to be from home-schooling environments. He also entertains groups of mineral enthusiasts, especially in the summer. The Bethel museum’s long-term goal is similar to Perham’s.

“We’re going to continue to collect,” Francis said. “We’re designing exhibits, we’re going to install them and open to the public, and then we’re going to shift into a whole other set of gears and really develop education programs for the schools and the general public.”

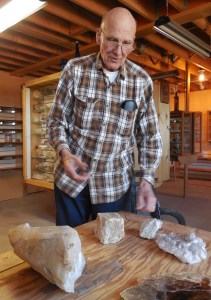

Perham called the original collection his “Cadillac” pieces, but for most of March he has been walking back and forth from his house to storage trailers across the road selecting “Ford and Chevy” specimens to refill the basement shelves emptied by the mineral museum sale.

“At 82 years old I can go mine right across the street,” Perham said. “It’s hard to beat that.”

Perham said he hasn’t looked into some of the stored boxes in the trailers since the 1960s. The new collection will be unique because Perham said he mined every piece.

There might be more “Cadillac” mineral specimens to be found within the local granite.

“You could actually be walking over Utopia, but you’d never know it, if you didn’t blast it or didn’t have an excavator to dig it down, or drill into it,” Perham said.

Perham knows how to do those things, he is an expert regarding the geological indications to look for, and he has always enjoyed support from a crew that has been somewhat transient, but eager, over his many years of mining.

Even at his advanced age, he’s promised to be back at work in the hills of Greenwood this summer looking for pockets of Maine pegmatite minerals with his friends.

“It takes a lot of help to do the job,” he said.

Polishing a gem in Bethel:

The Maine Mineral and Gem Museum is currently under construction at 99 Main St. in Bethel. When finished, the museum will be a year-round center with extensive exhibits on Maine’s geological history and displays of the state’s renowned mineral and rock collections, including the Frank Perham “Cadillac” collection.

The museum will also feature a two-ton beryl crystal, on loan from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, discovered in 1929 at the Bumpus Mine in Albany Township, and a display of the first gem tourmaline found in North America at Mt. Mica Mine on Paris Hill in 1820.

For more information about the museum, go to mainemineralmuseum.org or call (207) 824-3036.

Comments are no longer available on this story