As another Martin Luther King Jr. Day approaches, public comments from high-profile leaders in the past year have encouraged more open prejudice, Maine’s former hate crime prosecutor said this week.

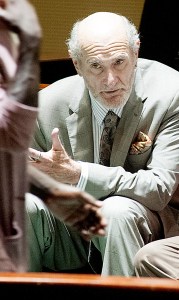

What leaders say makes a difference, said Steve Wessler, who served with the Maine Attorney General’s Office and works nationally and internationally with schools and communities to reduce prejudice and hate crime

“The level of spoken bias toward students of color, Muslims and Jews is high” across the country, he said Thursday. “It’s hard to say if it’s higher. I’ve been with students in past weeks in western United States who felt bias has increased over the year during the campaign.”

In Maine, Gov. Paul LePage made headlines for comments about black men “named D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” coming to Maine from Connecticut to sell drugs, and about immigrants working the welfare system. LePage spokesman Peter Steele has said the governor wasn’t talking about race, but the toll drugs have on children.

And, President-elect Donald Trump’s comments about Muslims and Mexicans have raised concern.

“For lots of people they take those messages and say, ‘I’m able to express my stereotype. It makes them freer” to think and say negative things about others, Wessler said. “That’s the danger. Leaders are important. Their messages can be helpful or unhealthy.”

While Maine isn’t embroiled in racial or police protests like other many parts of the country, the state’s criminal justice system makes it hard for blacks and minorities to get a fair shake, Lewiston defense lawyer

said, a situation that has been studied by criminal justice advocates for years.

The Constitution guarantees anyone charged with a crime to have a right to a fair trial by an impartial “jury of their peers,” Sharon said.

“Maine makes it very difficult to secure a racially unbiased jury,” he said. “The clients see it. The lawyers see it.”

At the time of the 2010 Census, 94.4 percent of Maine’s population was non-Hispanic white. Just 1.1 percent were African American, and 1.3 percent Hispanic or Latino. The growing immigrant population is shifting those statistics, but Maine remains overwhelmingly white.

Because of their life experience, minorities bring different perspectives to a jury than whites, Sharon said.

Jurors are selected for duty through driver’s licenses. If a defendant is black or a minority, it’s tough to get “a jury of peers,” Sharon said. The court needs to figure out a way to secure more people of color to be chosen as prospective jurors, Sharon said.

Making the problem worse are public comments from politicians.

LePage’s comments about “black drug dealers from Connecticut” has made it tough in some drug trials to pick jurors, Sharon said.

Because of these and other comments, Sharon is concerned about client Ashraf Eldeknawey.

Last year, federal investigators alleged in an affidavit that Eldeknawey was involved with preparing fraudulent tax returns at a Portland halal market. Federal investigators said the man was an associate of the market’s owner, who was using his Ahram Halal Market for a “cash-back” scheme to convert food stamps into cash.

While the case was being investigated and before any charges were filed, LePage accused the Maine media in October of covering up welfare fraud and offered to release the federal affidavit to anyone, Sharon said.

“He made a big deal of it. He said immigrants were working the welfare system,” Sharon said.

He said his client maintains his innocence. As of Jan. 12, the case remains under investigation and no charges have been filed.

If charges are filed, Sharon said he’s concerned about getting an impartial jury. “They might be adversely affected because LePage presumed both our clients’ guilt,” Sharon said.

Unlike even five years ago, people are seeing more blacks being shot and beaten across the country, but that doesn’t necessarily mean more is happening, said Michael Rocque, Bates College assistant professor of sociology and co-chairman of this year’s MLK Day at Bates on Monday.

His perspective is that racism has not lessened. “It’s not been great. We know there’s more exposure to discord.”

While good data on the past year isn’t available, he said, what is clear is there’s more exposure in the media, including social media.

“On my Facebook and Twitter I see video of shootings, whereas that wasn’t the case in the past,” Rocque said. Seeing more graphic violence tends to entrench people “into whatever camp they’re in,” he said.

As MLK Day approaches, Wessler is encouraging people to reflect on the work of Martin Luther King Jr., to speak up when hearing racist comments.

It doesn’t matter if it’s about Catholics, Muslims, blacks or Hispanics. When someone says something degrading about any group, “turn to somebody and in a calm voice say, ‘I don’t want to hear that language. That’s hurtful to me and others,’” Wessler said. “That’s how you stop it.”

When he was an assistant attorney general for Maine investigating serious hate crimes, he almost always found a culture where degrading language was widespread, he said. Language is how it starts.

“If people think it’s OK to say racial slurs and nobody intervenes, somebody gets the idea to do something more aggressive.”

That’s how someone gets seriously hurt or killed, “or a building gets burned down,” Wessler said. “We all have a role in language people use.”

Hate crime incidents in Maine:

2015 38

2014 28

2013 25

2012 56

2011 58

2010 66

2009 49

2008 64

2007 72

2006 59

*Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting

Comments are no longer available on this story