One summer day in 1898, while Lewiston Mayor William Newell and his family frolicked on vacation at the Maine shore, some children taking a cow to pasture saw a package on the doorstep of the mayor’s home at the northeast corner of College and Holland streets.

Curious, they went up to see what it was — and giddily discovered the package contained candy.

Since the mayor was away, and his house closed up, the youngsters decided their best course of action was, not surprisingly, to eat it.

They weren’t especially selfish children so they agreed to divide up the unexpected find evenly, then proceeded in due course to gobble down all of it.

Each of them got dreadfully sick.

Fortunately, a nearby physician “saved their innocent little lives,” the Lewiston Evening Journal reported.

The police were notified quickly about the potentially poisoned candy, which they soon learned had been spiked with enough arsenic to kill someone had the package been shared less widely.

The newspaper said Newell, too, was soon told of the crime.

“No one would have blamed him,” it added, “had he admitted he felt an icy hand about his heart as he thought of the possibilities about what might have happened had his family been home, and his own darlings found the poisoned candy.”

About the same time, the wife of longtime Lewiston City Judge Adelbert Cornish found five pounds of sugar at her back door, done up in a bag the same way a grocer might have delivered it.

A little note attached said merely, “Cornish,” as a harried shopkeeper might have written it.

When the judge returned home, his wife told him, “I found the sugar. But what made you order such a small amount? You generally order more. Were they nearly out of it?”

The judge answered, “I didn’t order any sugar.”

Cornish then looked carefully at the package and decided it had “a peculiar appearance” so the couple put it aside and out of reach.

After the poisoned candy became known, Cornish handed the bag over to authorities, who sent it to a Bowdoin College professor to analyze.

Laced among the sugar, Professor Franklin Robinson discovered, was a product called “Rough on Rats,” so toxic it would have killed anyone who had even a spoonful of it.

As if that wasn’t enough, a bottle of whiskey, sent anonymously from Boston, showed up at the door of former City Marshal Herbert Teel, who noticed some sediment had settled at the bottom. He, too, grew suspicious.

Robinson checked it out and found, to nobody’s surprise, that it also contained “Rough on Rats” in dangerous quantities.

It didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to see a likely connection between the three incidents. Nor did it require much thought to recognize a serious threat lurked within the community.

Henry Wing, the new city marshal, began investigating along with Detective Fred Odlin.

What Wing found turned out to be, as the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle in New York put it in 1899, “one of the most sensational criminal cases ever known in Maine,” a case so lurid it made headlines across America and transfixed Lewiston for months.

A ‘mean and sneaky’ criminal

Authorities discovered that a wealthy Lewiston man had tried unsuccessfully to poison a judge, a mayor and a former marshal as part of a campaign of terror he launched against some of the city’s leading figures.

Officials recognized that a series of anonymous letters sent to many of Lewiston’s leading citizens probably had something to do with the plot. Someone was also painting fences and brick walls with threats against the same men.

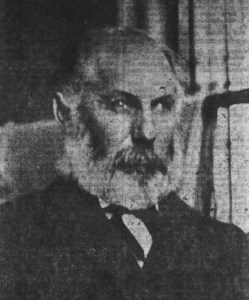

The Pinkerton Agency was called in to decipher the clues and find a suspect. It didn’t take long for them to zero in on a man tried for assault and battery two years earlier: a wealthy but not-quite-sane resident named George W. Pierce.

Pinkerton experts determined he’d bought the typewriter used for some of the letters, penned some of the others and got a woman named Maude Warren to write still others, apparently oblivious to what they meant.

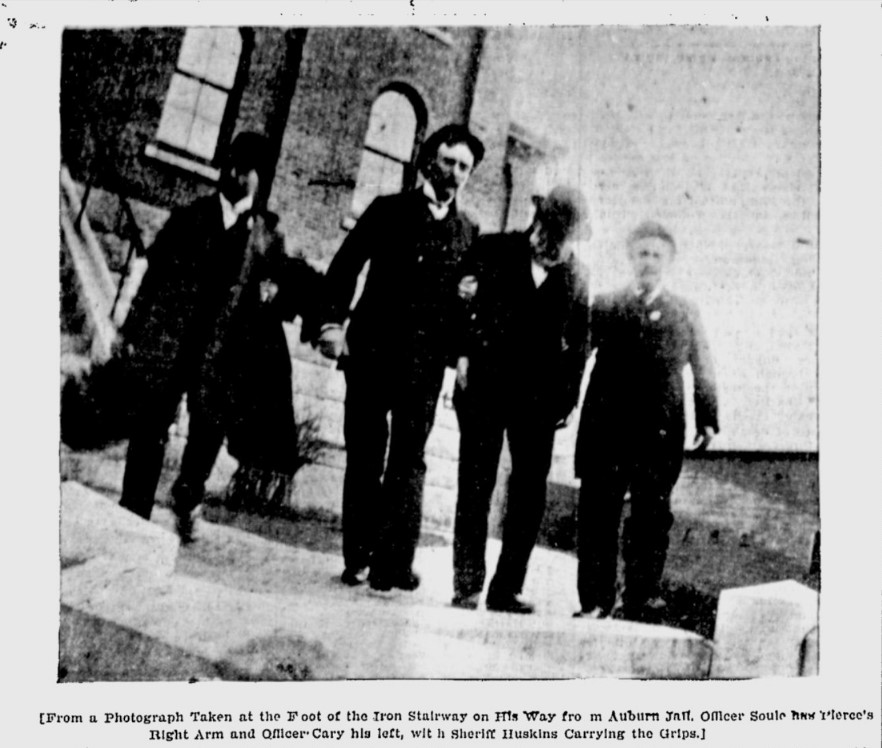

Hauled to jail early in 1899, Pierce wound up facing charges for attempted murder and criminal libel in a case that drew lurid coverage in newspapers across the country.

In a “mean and sneaky manner,” the Lewiston Evening Journal reported early in the trial, Pierce had put arsenic in sugar left at the the home of Lewiston City Judge Adelbert Cornish, doctored a bottle of whiskey delivered to former City Marshal Herbert Teel, wrote scurrilous letters and signs smearing city leaders, and dabbed their homes with black paint. Details about the candy left at Mayor Newell’s house would come out later in the trial.

A much-watched trial

The trial, in May 1899, lasted less than a week, with much of it taken up with detailed talk of writing styles, typewriters and other mundane but necessary proof that Pierce had been behind the scheme.

Several witnesses said Pierce insisted that if he had done any of it, it was because he was crazy.

But the testimony showed a man who had hits wits about him.

A detective, for example, said Pierce had several times offered him large bribes to help him escape from the Androscoggin County jail.

At one point during the case, Mayor Newell said on the stand that he confronted Pierce about the poisoned candy the children found outside his house.

Newell said he told Pierce if he ever did such a thing again “you will never need to be tried by a judge and jury for I will take a pistol and blow your damned brains out.”

In the end, a jury quickly convicted Pierce and a judge sentenced him to 38 years in the State Prison in Thomaston.

“I am convicted by a pack of lies,” Pierce told the court at his sentencing. “Everything about my trying to kill anyone is a lie.”

Before he was hauled off, Pierce told a Journal reporter that “everybody around here hates me. I don’t see why it is.”

Long after the trial, Arthur Staples, editor of the Journal, recalled that Pierce “had a mania” that made him determined to “get even” if anyone harmed him.

“Once, a woman, a poor neighbor, was suspected by him of taking a stick or two of cordwood from his pile,” Staples said, so Pierce “loaded sticks of wood with enormous loads of (gun) powder and blew up her domain, with serious injury and much loss.”

As Staples noted in his 1929 column, “The courts do not permit one to take such methods of reprisal. One is supposed to convict the party in the court, not on top of an explosion.”

But Pierce was not a man to rely on the legal system for justice.

Pierce in prison

Just a year into his long sentence in 1900, the Journal said a visitor who saw Pierce behind bars in Thomaston called him “the most dejected-looking man he ever saw.”

If former Journal editor Sam E. Conner’s sources were on target, it’s no wonder.

Conner wrote that Pierce “became the most despised prisoner” held by the state. “Neither inmates nor officials had any use for him.”

He said that Pierce “was always doing mean things, trying to chisel from others. If he could make trouble for another convict, he did so. If one of them tried to be kind to him, he would return it with a mean act.”

“He’s an excellent man to be afraid of,” wrote fellow prisoner Paul Dennison in 1904. “There’s a cold glitter of those queer eyes of his that makes me think it would not be salubrious to vex him.”

As a wealthy man, Conner said, Pierce “could have provided himself with delicacies” if he had wished.

Instead, though, “he would hunt through the swill buckets, picking out waste food and eating it.”

By 1910, perhaps Pierce was doing better.

At a hearing that spring to consider his appeal for a pardon, Attorney L.W. Fales of Lewiston told members of the state panel that Pierce “has paid the penalty for his wrongdoing” with 11 years in state custody for a crime he committed while insane.

Charles Boothby of Lewiston, a nephew of Pierce, said he’d spoken with his uncle several times. He insisted Pierce was “thoroughly penitent,” but could not remember the case against him.

Boothby said the older man vowed if given his freedom “to lead an upright life” and be “a credit to the community.”

Pierce told his nephew “he would not hurt anyone” if released.

Asked about Pierce’s unruliness at Thomaston, Fales said his client “chafed under confinement.”

Androscoggin County Attorney Frank Morey wasn’t buying any of it.

“The community would not be safe with George W. Pierce at liberty,” Morey told the pardon board.

He pointed out that it was simply luck that kept several people from dying at Pierce’s hands and that a dozen other men had been “marked for slaughter” in a list kept by Pierce.

Authorities obviously agreed with Morey. They refused to free Pierce.

A lonely death

On July 4, 1910, the 69-year-old Pierce died at the state prison.

The Lewiston Daily Sun called him “an old man” who still held considerable property in Auburn and Lewiston.

Pierce’s remains were sent by train the day after his death. They were taken to Boothby’s home on Bates Street, where a funeral was held by the pastor of the Pine Street First Baptist Church.

A handful of relatives listened as the Rev. S.A. Blaisdell spoke a few words.

He told the small gathering to “trust in God thru all thy days/ Fear not, for he doth hold thy hand/ The dark the way, still sing and praise/ Sometime we’ll understand.”

Pierce was laid to rest at Riverside Cemetery beside his mother and father.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your Sun Journal account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.