OTISFIELD – Marine Corp and Vietnam veteran Bill Griffin’s recent Honor Flight to Washington D.C. came about accidentally. He almost sat the trip out.

The weekend, spent with veterans from around the country, opened a path to emotional healing he had not anticipated.

The welcome Griffin and 77 other veterans received when their Honor Flight returned to Bangor International Airport was as remarkable as the trip, and far different than what he experienced during the Vietnam War.

Griffin’s improbable Honor Flight began a couple of years ago. A few days after completing his trip in April, he agreed to share his story with the Advertiser Democrat.

Accidental application

“I had learned about Honor Flight and thought it would be cool to go down – as a guardian,” he says, speaking about his recent saga from the beginning. “I began filling out the form (online), and it turned out I was over the age limit. When I got to that question, I just stopped, as I was just over the age limit to be a guardian.”

Then, earlier this year Honor Flight Maine made a phone call he was not expecting – he had not completed his form, but he was confirmed on their list to go on Honor Flight.

Not as a volunteer guardian but as a Vietnam veteran.

After explaining to the caller he had been looking to volunteer and not be a guest of honor, she encouraged him to complete his application anyway.

Griffin submitted his information, but he was ambivalent about taking the trip. He had been to the veteran memorials in Washington D.C. years ago – twice, including with his family in the 1980s when his two sons were still in school. He was not keen to return to the capital to see something he had already experienced.

Griffin served in the U.S. Marines from 1966-1975 and did two abbreviated tours in Vietnam.

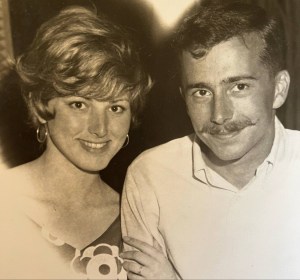

Griffin’s wife Pat told him he needed to go. But non-veteran spouses are not allowed to serve as guardians, so Griffin off-handedly texted his sons, Trent and Nate, asking which of them wanted to go.

Trent, an Army National Guard veteran, answered first, thus beating out his younger brother.

“I had reservations, all the way to the last day,” Griffin said. “I just didn’t know if I really wanted to. I just felt that I had been there and maybe it’s not such a big deal. And I was surprised.”

Pat, who remembers what it was like for him to return home from Vietnam, was not about to let her guy miss the opportunity.

“I encouraged, but then I had to put my foot down and say, ‘you’re going,’” she said. “I told him, ‘your place has been reserved, Trent has set his time aside.’”

So Griffin packed his bags, collected his son and the two headed for Bangor.

“There was one veteran there with a logo on his hat belonging to the sister battalion I was in,” he said. “He was a corpsman with the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Marines. And I was there at about the same time, in the 2nd Battalion. So I went right over to talk with him and we had a good time. We really connected.”

Honored

Griffin’s trip departed Bangor April 25. Those familiar with Honor Flight know it’s an itinerary packed weekend with a tight schedule, and it can be somber at times.

The Maine veterans’ tour started Saturday morning with a stop at Arlington National Cemetery and included a viewing of the Changing of Guard and wreath laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Solder.

From there the group visited the Marine Corp, Air Force and U.S. Navy memorials, the Korean War and Vietnam Memorial walls, The World War II Memorial and finally the Military Women’s Memorial. The memorial visits were punctuated by group meals and ceremonies.

Griffin laughed, “It’s by design, they don’t want anyone wandering off and getting lost so they keep us pretty busy.”

Joking aside, Griffin was impacted during the trip in ways he had not expected.

“I had seen the changing of the guard before, but this one was pretty emotional. It was being with a group of veterans,” he said. “The four oldest veterans with us placed a wreath in front of the memorial.”

But he also took the time while there to honor his great uncles, John Arthur and Ray Stowell of Freeport, by posting a picture taken as they left home to serve in World War I. Arthur Stowell was killed in action, and while Ray survived the war, he lived the rest of his life with consequences of mustard gas poisoning.

At the Korean War memorial Griffin found the names of men he had known in Vietnam and shared them with Trent.

“I wanted to go to the Korean Memorial first,” he said. “The wall has faces taken from photos of people who were there, and the bronze statues there are of veterans. That one means a lot to me.”

While recalling his walk to the Vietnam Wall Memorial, Griffin shut down. For a few moments, the only thing he could say: “feel free to comment on that, too.”

Then he drifted back to the 1980s when he read about the memorial before seeing it, before he was able to further describe his present-day visit.

“We walked over this little rise, and to the left you see it and it starts to expand until you’re at the top of the rise and can see the whole memorial,” Griffin said, carefully choosing his words. “It just gets me. I’d walked it once before and it still gets me.”

He carried with him the names of Marines who had served in his unit between 1962 and 1975, including some he did not personally know. But there was one person he especially wanted to pay tribute to.

“Larry (Duke) and I served in Okinawa together before going to Vietnam,” Griffin said. “He was killed the day I had left to go on R&R” to see Pat in Hawaii.

After a few minutes Griffin then was able to share a little more about his buddy Larry. “Often, one of us would be assigned to take mail out to our remote sites by helicopter. We’d take codes to reset the radio equipment each month. Sometimes I would do it, sometimes it was someone else.

“On that day, I was going on R&R. Larry wanted to go out because he had about a month left and then he was going home to get married.

“I can see him when I think about it. The helicopter was sitting on the pad, running. Larry and four other guys were waiting to go up the ramp in the back of the helicopter, and I was getting in a Jeep with a guy driving me to Da Nang.”

When he got to Da Nang, he saw black smoke rising back in the distance and knew something bad had happened. But he would not learn until he returned that Duke was one of four men onboard who were killed when the helicopter crashed.

A docent helped Griffin and Trent locate Duke’s and others’ names, leading them from one to the next so they could make etchings.

One of his more indelible events at the memorial happened as Griffin’s new friend from the Third Battalion was running out of time to find the names he came to see.

“A little Vietnamese kid came to him and told him he would help,” Griffin said. “He comes to wall with his parents and siblings to help people visiting. Their story is that they want their children to know how it is…”

His voice trailed off once more for a few seconds before he could continue. “…How it is that they can live in this country,” he whispered.

Pat picked up the story while her husband took a minute for himself. “Isn’t that the coolest thing to do? To show that appreciation for the U.S. soldiers. Two, three generations later. Those kids approach those veterans, and they know the drill, exactly what to do.”

Homecoming celebration

In a weekend of meaningful moments, Griffin felt the biggest one of all after getting off the plane in Bangor Sunday afternoon, complete with an exit ramp miscue that required everyone aboard to disembark from back to front to maintain stable weight distribution of the aircraft.

“We had a line of dignitaries waiting to greet us,” he said. “The governor was there, along with various colonels and generals. There were other politicians, although I didn’t know them. And they were all telling us ‘thank you’.

“Then we went from one hangar to another, and it was full of people,” here Griffin paused as he recalled the moment. “Full of people to welcome us back. We got to walk by them and wave. Then we were all given a seat while people gave speeches.”

Griffin’s welcome back to Maine following his Honor Flight meant the world to him. It was much different than when Pat picked him up during his return to Maine while on leave in 1970, although that day could have served as the final scene of a movie.

Pat relayed that chapter, as she was the entire welcoming at Boston Logan International Airport to greet him.

“One thing Bill said, about the highlight of coming back to that huge reception of people showing how grateful they were for the guys’ service,” she said. “When he came back from Vietnam, that was a time when some veterans didn’t even go home because they weren’t welcomed.”

She expected her husband would arrive in Portland. But after learning he had endured multiple flight delays over four days and the furthest east he could get was to Boston, she commandeered her father-in-law’s car and rushed down to Logan.

“Of the whole airport, I had no clue where he was. I just pulled up in a no parking zone at what looked like the biggest part of the airport, ran up the stairs, and there he was.

“We had been married 12 days (before Griffin was called to his second duty in Vietnam). It was almost miraculous – there he was! Those few people who were around, they clapped for us. But they just happened to be there.”

“You hear stories about people coming back and being treated so badly,” Griffin said. “I didn’t notice that. I felt ignored.”

The one exception of feeling invisible came during the trip home from his first tour. Seated in a bar by himself, a former Marine, who undoubtedly understood Griffin’s experiences and future, bought him a beer.

Honor Flight Maine provided Griffin with the opportunity to pay his respects to friends he made and lost a lifetime ago, as well as a sense of belonging to something great that many like him downplayed as they coped with the grim aftermath of war.

As Pat noted following his interview with the newspaper, his journey – and talking about it – have helped unlock grief carried for more than half a century.

“It was a really neat experience,” Griffin said. “This morning, I emailed the organization to thank them and told them I’d still like to go as a guardian. When I got to D.C., I realized some of those guardians are a lot older than I am!”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your Sun Journal account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.