In 1970, Scanlan Magazine published a story by Hunter S. Thompson titled “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.” Today, the article is cited as the origin point of “gonzo” journalism, a style of journalism that places the reporter at the center of the story. But it was also the beginning of something else.

It was the first time Thompson met Ralph Steadman, an English artist who had been hired to illustrate the races for the magazine. As Thompson detailed his own exploits, he also recounted the way Steadman observed and photographed and drew the rowdy crowd.

“I left Steadman sketching in the Paddock bar and sent off to place our bets on the sixth race,” Thompson wrote in the article. “When I came back he was staring intently at a group of young men around a stable not far away. ‘Jesus, look at the corruption in that face!’ he whispered. ‘Look at the madness, the fear, the greed!’ ”

Steadman and Thompson worked together for years, and their names would become synonymous with the unconventional style of journalism that allowed both men to satirize the world around them.

Bates College Museum of Art is host a traveling exhibition of Steadman’s work that presents a more expansive view of the artist’s career.

“And Another Thing,” which is open until Oct. 11, includes frenetic pictures that accompanied Thompson’s wild storytelling. But it also features Steadman’s early cartoons, sardonic caricatures of politicians, striking illustrations from Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland,” whimsical drawings of animals and more.

Sadie Williams, the artist’s daughter who now oversees his collection, said people often do not realize the breadth of her father’s work.

“People think they know Ralph Steadman’s work,” Williams said. “Then they go, ‘That’s not Steadman.’ Because they don’t know.”

‘I WORKED WITH CONVICTION’

As a boy, Steadman felt the sting of the cane wielded by his harsh headmaster. The experience made a lasting impression.

“He doesn’t like a bully,” Andrea Lee Harris, who co-curated the traveling exhibition, said.

He developed his technical drawing skills in part during his time in the Royal Air Force. In 1959, he began studying art at East Ham Technical College in London. A mentor encouraged him to draw constantly. Steadman created detailed sketches at the Natural History Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and those pencil drawings of dinosaur bones and stately arches are represented in the exhibition.

He started making his name as a cartoonist, and his work became increasingly political and nuanced. A biographical publication released in conjunction with “And Another Thing…” includes his reflection on this time.

“When the 1960s got underway, I felt pretty hopeful and even dared to imagine that each new drawing was a nail in the coffin of old values or rather old patterns of behavior which were full of privilege and injustice,” Steadman said. “It’s a strong feeling when you’re young. You really believe that things will change. So, I worked with conviction. It genuinely felt like a cause.”

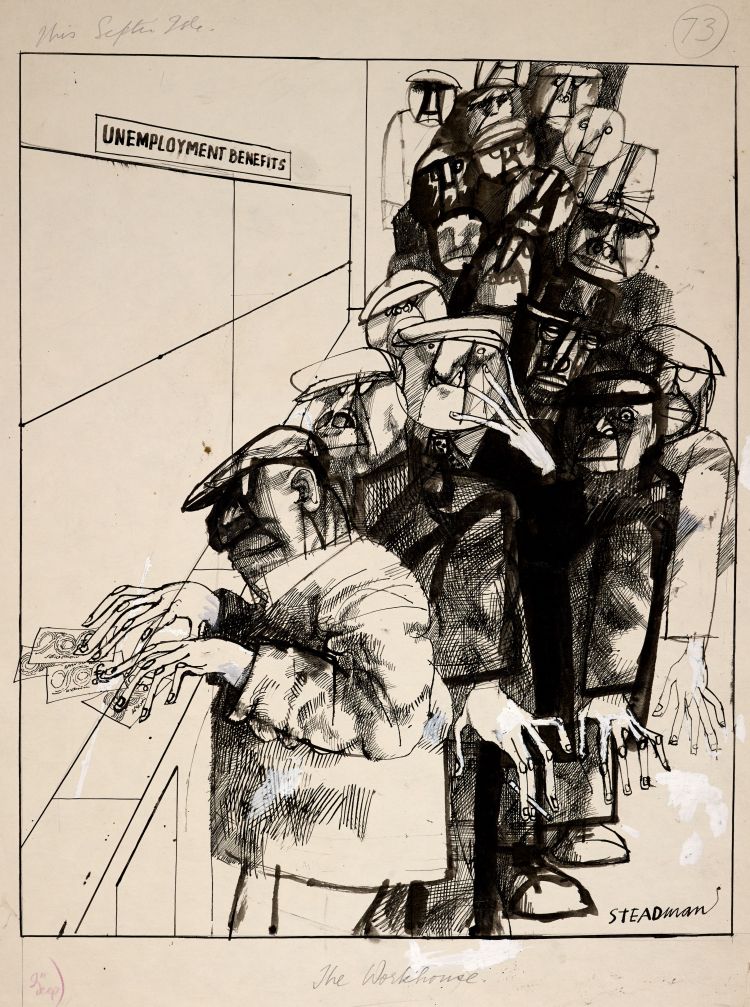

One early example is a circa-1965 drawing of people waiting in a line at the unemployment office. Harris pointed out the long fingers of the waiting men, the jittery atmosphere of the scene — details that spoke to the economic anxiety of the moment.

“You can feel the agitation in the crowd, in the eyes, in the way they’re all backed up,” Harris said. “They’re all in this sense of stress, suffering. You can feel it in the drawing.”

The installation is full of political satire that spans the artist’s lifetime and feel relevant in any era — from a 1974 drawing that observes the emergence of student power, to a 1977 image of police officers bearing grotesque faces and beating a man on the ground, to unflattering caricatures of American presidents. The most recent in that series is from 2023, when the artist used President Donald Trump’s mugshot as the source material for a drawing titled “Rotten Blot.”

“He said, ‘Ugh, I’m going to have to draw the man,’ ” Williams said.

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Steadman’s lines are deliberate, decisive, rendered in ink from the empty bottles that are on display in the gallery. He isn’t one to erase, Harris said.

“You can really feel the artist’s presence in the work,” Harris said. “I think that’s what people gravitated toward that loved the work but also that didn’t like the work, because there were these other illustrators doing very clean lines and finished work, and he was doing things that were more active and in your face.”

Boston Globe editor Bob Cardoso coined the term “gonzo” journalism in 1970 when Scanlan’s Monthly published the piece Thompson and Steadman created about their trip to the Kentucky Derby. It came to mean the kind of highly personalized journalism that focuses on the writer’s experiences of events.

Thompson’s writing embodied gonzo journalism, and Steadman embodied Thompson’s writing.

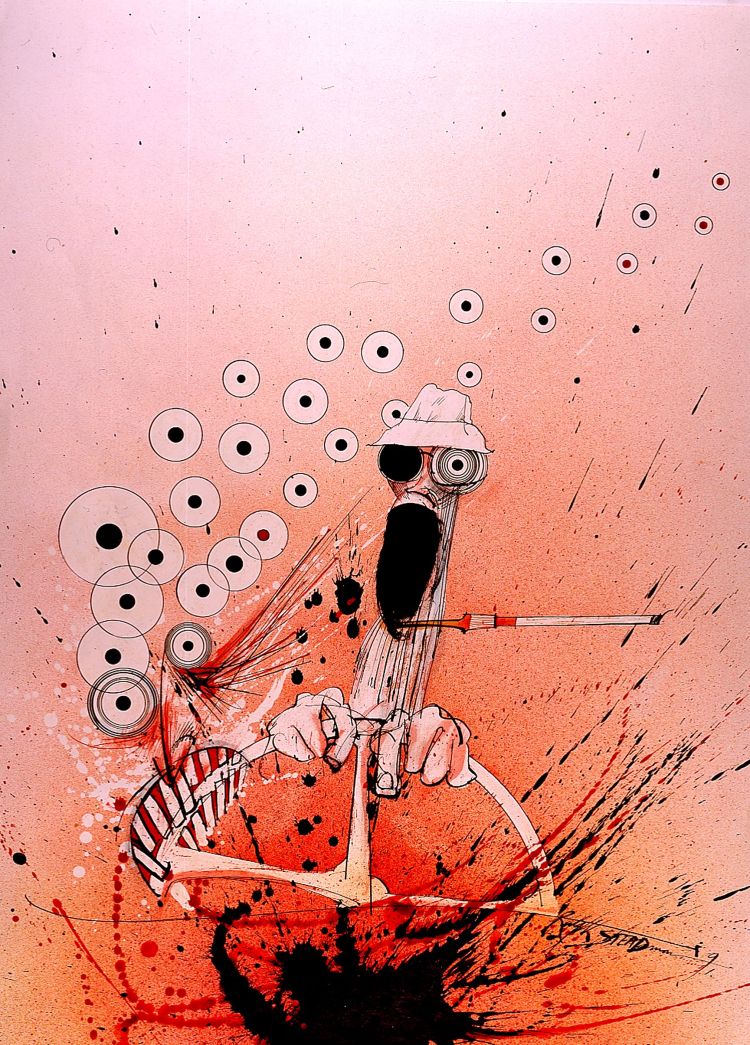

They often worked together, including when Steadman illustrated Thompson’s book “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.” (Steadman did not, however, accompany Thompson on that psychedelic road trip.)

Most people would know Steadman’s work from small reproductions — on the pages of “Fear and Loathing,” for example — but the original drawings are much larger than a paperback novel. And they are definitely larger than the smaller sketchbook pages of his younger days.

Williams and Harris said his paper got bigger because he was responding to the expansiveness of the American landscape, and he also became more comfortable with negative space on the page. But he also felt free to express himself on a larger scale.

“He just needs more room to express his ideas,” Williams said.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE

This full picture of Steadman might be new to some, but it is one Williams has always seen.

“My childhood just resonates through these walls,” Williams said.

She learned to swim in Hawaii when her father and Thompson were working on what would later become “The Curse of Lono.” She said Laila Nabulsi, Thompson’s girlfriend at the time, taught her. She remembers the year that her father had a broken leg and passed the recovery in their living room drawing the images for “I, Leonardo,” his illustrated biography of Leonardo da Vinci. (“I quite like making things, and I think he did too,” Steadman said. He even built a flying machine from an old nylon tent and bamboo as part of his research in order to get in touch with his subject, according to the book published with the exhibition.)

“I’ve got so many memories of being in bookshops with my dad signing for hours and hours,” she said. “And he would talk to everybody, sketch in every book and engage with every single person and wouldn’t go until the queue was done.”

“And Another Thing…” came to Bates College because the now-retired director Dan Mills met Williams at an earlier exhibition of Steadman’s work. They got to talking and planned to bring the show to Bates in 2020. The pandemic derailed that exhibition, so this one is a long time coming.

Anthony Shostak, education curator and interim operations manager at the museum, said he expects to see all kinds of visitors — students of everything from environmental science to journalism, adults who know “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” and kids who will appreciate the pile of children’s books available in the downstairs gallery. There are 149 objects in the show.

“Ralph’s work is very wide reaching in terms of subjects, and that makes his work especially interesting at an academic museum like Bates College,” Shostak said. “There are literary references in Ralph’s work. His work is engaged with history. You can see environmental connections, social justice connections. This exhibition can speak to a lot of disciplines.”

Williams is now the director of the Ralph Steadman Art Collection. Her father is 89 and slowing down. She spends just as much time talking about his gonzo days as she does his illustrations for “Alice in Wonderland” or his images of endangered animals.

“That’s the nicest bit for me, that you can show people a side they didn’t know existed,” she said.

IF YOU GO

WHAT: “Ralph Steadman: And Another Thing…”

WHERE: Bates College Museum of Art, Olin Arts Center, 75 Russell Street, Lewiston

WHEN: Through Oct. 11

HOURS: Summer hours are the museum are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday. It is closed Sundays.

HOW MUCH: Free

INFO: Public programs in conjunction with this exhibition include film screenings of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” the 1998 film based on Thompson’s book, and “For No Good Reason,” a 2012 documentary about Steadman. For more information, visit bates.edu/museum or call 207-786-6158.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your Sun Journal account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.