LEWISTON — Every weekday after school at Connors Elementary in Lewiston, you’ll find a group of kids playing soccer — and hopefully gaining life skills in the process.

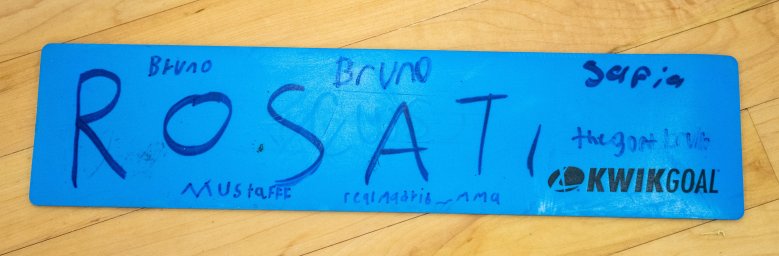

Through the nonprofit Rosati Leadership Academy, Lewiston students gain soccer experience as well as social, emotional and leadership skills. The program infuses life lessons and positive coping behaviors into a futsal model — a fast-paced version of soccer played on hard surfaces — to support students in and out of the classroom.

“When you play a team sport like soccer, you have countless points for potential disagreement,” said Noah Riskind, the academy’s assistant director and men’s soccer coach at Southern Maine Community College. “Team sports and sports in general are just such a great teacher. You learn how to lose, to learn how to pick yourself back up, to be an effective leader.”

Rosati Leadership Academy, a nonprofit, is working to make soccer accessible to Lewiston youth free of cost. Offering after-school programming for elementary and middle schoolers at Connors gym, Rosati holds practices five days a week.

With emphasis on free play, Rosati focuses on developing the whole player. Using soccer as a learning space, sessions are structured to equip kids with social and emotional skills they can bring to the classroom.

Chris White, Rosati’s founder and director, wants the sessions to be a “laboratory of leadership.” He hopes the program “creates an environment where kids can experiment with making better decisions.”

“It’s almost like training wheels,” said White, describing how the academy creates a space for students to test resolving issues with peers outside of a traditional school setting. Sessions require students to work together regardless of their relationship in the classroom.

The coeducational program has served hundreds of students, allowing them to play soccer free of charge. Put simply, White said, the goals of the program are better grades, better behavior, better life outcomes after high school, and, of course, better soccer.

Teaching opportunities

Coming from Durham, North Carolina, White hoped to create a program to support educators.

“I love teaching and I consider myself a teacher still,” said White, who taught science and social studies.

During his time working in public schools, White identified a need for conflict resolution skills. He wanted to create a program around social and emotional learning that blurred the lines between class and after-school sports.

Former Lewiston High School boys soccer coach Mike McGraw was on the same page. Around 2013, McGraw had an idea to run an after-school program for kids that “was free and involved soccer, but also involved academics and good student behavior.”

McGraw, who led the Lewiston High School program to three state championships between 2015 and 2019, saw the potential impact of this program in Lewiston, a city with a rich soccer culture. McGraw wants players “to take the lessons that the game teaches and the discipline that they learn, and bring it into the classroom.”

With a joint vision identified, “the hand of God was like, ‘You’re going to Maine,’” White said.

White was inspired by Chris Rosati, his former high school soccer teammate at Durham Academy. After Rosati was diagnosed with ALS in 2010, he committed his life to benefaction. The nonprofit is named in Rosati’s honor.

The program was started in 2018 and received nonprofit status in 2020. It has thrived at Connors gym with the support of community collaborators, including the Lewiston Recreation Department, Lewiston Public Schools and the support of Fowsia Musse, executive director of Maine Community Integration, a Lewiston-based nonprofit that supports girls who are new Mainers, as well as their families.

Volunteer give, but can also benefit from Rosati

Darby Ray, director of the Harward Center for Community Partnerships at Bates College in Lewiston, said Rosati is a popular match for Bates student volunteers.

“It’s almost like therapy in there,” said Bates volunteer and first-year student Luca Balzano. A member of the men’s soccer team and recently awarded by the Harward Center for his work with Rosati, Balzano described the program as “a getaway,” and White as giving kids “the most beautiful couple hours.”

One thing that sets the program apart, Balzano said, is how it is led by the students themselves.

“It’s pretty cool,” he said. “There’s like 6-, 7-, 8-year-olds who have whiteboards or these sheets of paper and clipboards and they take attendance.”

“Adults are not (the ones) solving problems,” White said. Based on his experience, White discussed how teachers often struggle to resolve conflicts between students fairly because they “don’t get to see everything.”

White’s hands-off technique empowering students to settle their own disputes is a key feature in Rosati’s sessions. At the beginning of practices, team captains are elected to resolve conflict among peers and take a leadership role in practice.

Omar, a 12-year-old who has been with Rosati for five years, said he loves “how the kids have leadership and how the coaches are nice and help us get better.”

McGraw discussed the “responsibility” bestowed upon students. “I think that plays a huge role in just how the kids are going to handle things when they grow up,” Balzano said.

Middle school students even aid in practice. After aging out of the elementary school program, players kept returning. To accommodate these older students, Fowsia Musse came up with the idea of an alumni coaching network.

With a grant from Maine Community Integration, middle school students can return to be assistant coaches, helping with attendance, set-up and conflict resolution. They are paid in incentive cards that have daily obligations for coaches to complete. This system is self-sustaining and mutually beneficial for the program and the community: Rosati does not have to train new volunteers while middle school students get the opportunity for a paid job at a program they enjoyed.

Every practice begins with street soccer. “During street soccer, there are no rules,” Riskind said. “The kids are in charge. It’s just their opportunity to get creative and just kind of play however they want to play.”

Penalty cards and resolving conflict

Street soccer brings out the joy of the sport. It creates a space for students to step into leadership positions and enjoy each other’s company. Additionally, it promotes creativity.

In addition to its goals of providing free soccer and a safe space for kids to grow, Rosati combats a national narrative of “pay to play,” where the focus is on club soccer, which can be costly enough to keep some kids away.

“We feel in this country specifically, kids don’t play as much pickup as they used to and everything is so organized and structured,” Riskind said. “Street soccer is our way to just let the kids play, but also give them the ownership over it.”

However, for instances where students cannot self-regulate, Rosati has a card system. Just like soccer, where flagrant fouls are disciplined with cards, the program features red and yellow card penalties.

Yellow cards are minor infractions while red cards are major. Yet Rosati adds a unique layer to this disciplinary system. Cards are not only given out in practice; teachers at Connors have a right to hand out cards for students who are not behaving in class. Students with cards are supposed to report their penalty to White, who said he always takes a photo, encouraging an honor code system.

Conversely, if a student is performing well in school and getting along well with peers, they are given a green card. This gives them special privileges at practice.

The green card also repairs bad behaviors. Students who accumulate a certain amount of yellow or red cards from a teacher must obtain a green card from that teacher to mark their improved behavior. “We explode in positive ways around good things,” White said.

Students can also give each other yellow cards. If they both decide to give themselves a card, the two cards cancel out, marking the conflict as resolved.

A period of mindful breathing follows street soccer. Kids then speak on the mindfulness topic of the week like “letting go.” One student shared that a teacher called on someone before them despite having their hand up first. Instead of arguing, the student “let it go.”

Although Rosati began as a program for boys, it soon expanded to include girls. “Gender equity has been a big push for us,” White said.

Bates senior Heidi Nydam, a Rosati volunteer and member of the women’s soccer team, said it’s important for kids to have female coaches.

“I think that culturally and religiously there’s not necessarily representation of women in sports for a lot of the Somali families and so being there as an example of somebody who’s just a woman in soccer is important,” she said.

Nydam talked about the joy in sharing her love of soccer with the kids. “Soccer is something that has provided me a sense of belonging,” she said. “You can totally see that’s what’s happening to these kids and they’re finding themselves through soccer.”

White said it’s important to create a safe and inclusive space, reflecting on the historical and cultural diversity of Lewiston. “I think we’ve just created an environment of unconditional respect and celebration of different cultures,” he said.

The program works with many immigrant families, some who are not fluent in English. White said “those students sometimes have anger issues,” speculating that the language barrier contributes to this behavior.

He reflected on his own experiences with international schooling. White recalled going to school in Japan while his father, who was a professor, studied Japanese politics, giving him insight and sensitivity to the experience of the program’s non-English speakers.

“Do I know what it’s like to be in a classroom and not know what’s going on? Yes. Do I really know what these kids in Lewiston are feeling? Absolutely not,” he said. “I’m a white male from North Carolina, but I do have a lot of international experience and I hope that’s given me an open mind and a respectful heart towards different cultural diversity.”

Ebenezer Kwarteng, who works as a coach at Rosati, said the program “makes me feel like home.” Known as coach DJ to the kids, Kwarteng is a new Mainer from Ghana. Having grown up in an orphanage, Kwarteng hopes he can be a support system for many of the kids in the program.

As Nydam put it, Rosati gives students “a home for a couple of hours after school every day.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your Sun Journal account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.